Introduzione generale per la progettazione strutturale di dettagli in calcestruzzo

La progettazione e la valutazione degli elementi in calcestruzzo vengono normalmente eseguite a livello di sezione (elemento 1D) o puntuale (elemento 2D). Questa procedura è descritta in tutte le norme per la progettazione strutturale, ad esempio in (EN 1992-1-1 o ACI 318-19), ed è utilizzata nella pratica quotidiana dell'ingegneria strutturale. Tuttavia, non è sempre noto o rispettato che la procedura è accettabile solo nelle aree in cui si applica l'ipotesi di Bernoulli-Navier della distribuzione piana delle deformazioni (le cosiddette regioni B). I luoghi in cui questa ipotesi non è applicabile sono chiamati regioni di discontinuità o disturbate (D-Regions). Esempi di regioni B e D di elementi 1D sono forniti in (Fig. 1). Si tratta, ad esempio, di aree portanti, parti in cui vengono applicati carichi concentrati, luoghi in cui si verifica un brusco cambiamento nella sezione trasversale, aperture, ecc. Quando progettiamo strutture in calcestruzzo, incontriamo molte altre regioni D come muri, ponti diaframmi, mensole, ecc.

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 1\qquad Discontinuity regions (Navrátil et al. 2017)}}}\]

In passato, per il dimensionamento delle regioni di discontinuità si utilizzavano regole di progettazione semi-empiriche. Fortunatamente, negli ultimi decenni queste regole sono state ampiamente superate dai modelli tirante-puntone (Schlaich et al., 1987) e dai campi di sollecitazione (Marti 1985), che sono presenti negli attuali codici di progettazione e che oggi sono frequentemente utilizzati dai progettisti. Questi modelli sono strumenti meccanicamente coerenti e potenti. Si noti che i campi di sollecitazione possono essere generalmente continui o discontinui e che i modelli tirante-puntone sono un caso particolare di campi di sollecitazione discontinui.

Nonostante l'evoluzione degli strumenti di calcolo negli ultimi decenni, i modelli Strut-and-Tie sono essenzialmente ancora utilizzati come calcoli manuali. La loro applicazione a strutture reali è noiosa e richiede molto tempo, poiché sono necessarie iterazioni e si devono considerare diversi casi di carico. Inoltre, questo metodo non è adatto per la verifica dei criteri di esercizio (deformazioni, ampiezza delle fessure, ecc.).

L'interesse degli ingegneri strutturali per uno strumento affidabile e veloce per la progettazione delle regioni D ha portato alla decisione di sviluppare il nuovo Compatible Stress Field Method, un metodo per la progettazione assistita da computer dei campi di sollecitazione che consente di progettare e valutare automaticamente le membrature strutturali in calcestruzzo soggette a carichi nel piano.

Il Compatible Stress Field Method (CSFM) è un metodo di analisi del campo di sollecitazione continuo basato sugli elementi finiti, in cui le soluzioni classiche del campo di sollecitazione sono integrate da considerazioni cinematiche, cioè lo stato di deformazione è valutato in tutta la struttura. Pertanto, la resistenza effettiva a compressione del calcestruzzo può essere calcolata automaticamente in base allo stato di deformazione trasversale, in modo simile a quanto avviene nelle analisi in campo di compressione che tengono conto del compression softening (Vecchio e Collins 1986; Kaufmann e Marti 1998) e nel metodo EPSF (Fernández Ruiz e Muttoni 2007). Inoltre, il CSFM considera il tension stiffening, fornendo rigidezze realistiche agli elementi e copre tutte le prescrizioni del codice di progettazione (compresi gli aspetti di esercizio e capacità di deformazione) non affrontate in modo coerente dagli approcci precedenti. Il CSFM utilizza leggi costitutive uniassiali comuni fornite dalle norme di progettazione per il calcestruzzo e le armature. Queste sono note in fase di progettazione, il che consente di utilizzare il metodo del coefficiente di sicurezza parziale. In questo modo, i progettisti non devono fornire ulteriori proprietà dei materiali, spesso arbitrarie, come invece è richiesto dalle analisi FE non lineari, rendendo il metodo perfettamente adatto alla pratica ingegneristica.

Per promuovere l'uso dei campi di sollecitazione assistiti dal computer da parte degli ingegneri strutturali, questi metodi dovrebbero essere implementati in ambienti software di facile utilizzo. A tal fine, il CSFM è stato implementato in IDEA StatiCa Detail, un nuovo software commerciale di facile utilizzo sviluppato congiuntamente dal Politecnico di Zurigo e dalla società di software IDEA StatiCa nell'ambito del progetto DR-Design Eurostars-10571.

Strumenti di progettazione per l'armatura

Flusso di lavoro e obiettivi

L'obiettivo degli strumenti di progettazione delle armature nel CSFM è quello di aiutare i progettisti a determinare in modo efficiente la posizione e la quantità necessaria di barre di armatura. Per aiutare e guidare l'utente in questo processo sono disponibili i seguenti strumenti: calcolo lineare e ottimizzazione topologica.

Gli strumenti di progettazione delle armature considerano modelli costitutivi più semplificati rispetto ai modelli utilizzati per la verifica finale della struttura. Pertanto, la definizione delle armature in questa fase deve essere considerata una pre-progettazione da confermare/raffinare durante la fase di verifica finale. L'uso dei diversi strumenti di progettazione delle armature sarà illustrato nel modello mostrato nella Fig. 3, che consiste in un'estremità di una trave semplicemente appoggiata con altezza variabile soggetta a un carico uniformemente distribuito.

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 3\qquad Modello utilizzato per illustrare l'uso degli strumenti di progettazione delle armature.}}}\]

Analisi lineare

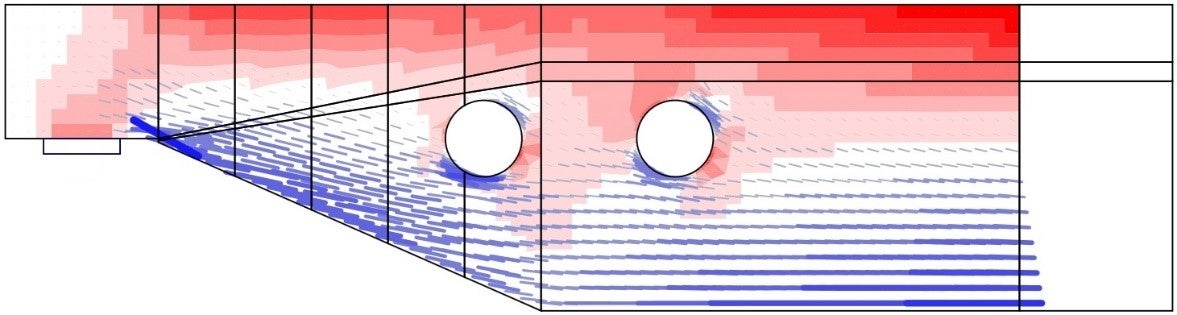

L'analisi lineare considera le proprietà elastiche lineari del materiale e trascura l'armatura nella regione del calcestruzzo. Si tratta quindi di un calcolo molto veloce che fornisce una prima idea della posizione delle aree di trazione e compressione. Un esempio di tale calcolo è mostrato nella Fig. 4.

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 4\qquad Risultati dello strumento di analisi lineare per la definizione della disposizione dell'armatura}}}\]

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{(rosso: aree in compressione, blu: aree in trazione).}}}\]

Ottimizzazione della topologia

L'ottimizzazione topologica è un metodo che mira a trovare la distribuzione ottimale del materiale in un determinato volume per una certa configurazione di carico. L'ottimizzazione topologica implementata in IDEA StatiCa Detail utilizza un modello lineare a elementi finiti. Ogni elemento finito può avere una densità relativa da 0 a 100 %, che rappresenta la quantità relativa di materiale utilizzato. Queste densità di elementi sono i parametri di ottimizzazione del problema di ottimizzazione. La distribuzione del materiale risultante è considerata ottimale per l'insieme di carichi dato se minimizza l'energia di deformazione totale del sistema. Per definizione, la distribuzione ottimale è anche la geometria che presenta la maggiore rigidezza possibile per i carichi dati.

Il processo di ottimizzazione iterativa inizia con una distribuzione omogenea della densità. Il calcolo viene eseguito per diverse frazioni di volume totale (20%, 40%, 60% e 80%), il che consente all'utente di scegliere il risultato più pratico. La forma risultante è costituita da tralicci reticolari con puntoni e tiranti e rappresenta la forma ottimale per i casi di carico indicati (Fig. 5).

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 5\qquad Risultati dello strumento di progettazione per l'ottimizzazione della topologia con volume effettivo del 20 e del 40}}}\]

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{(rosso: aree in compressione, blu: aree in trazione).}}}\]

Introduction to finite element implementation

The CSFM considers continuous stress fields in the concrete (2D finite elements), complemented by discrete “rod” elements representing the reinforcement (1D finite elements). Therefore, the reinforcement is not diffusely embedded into the concrete 2D finite elements but explicitly modeled and connected to them. A plane stress state is considered in the calculation model.

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 6\qquad Visualization of the calculation model of a structural element (trimmed beam) in Idea StatiCa Detail.}}}\]

Both entire walls and beams, as well as details (parts) of beams (isolated discontinuity region, also called trimmed end), can be modeled. In the case of walls and entire beams, supports must be defined in such a way that an (externally) isostatic (statically determinate) or hyperstatic (statically indeterminate) structure results. The load transfer at the trimmed ends of beams is introduced by means of a special Saint-Venant transfer zone, which ensures a realistic stress distribution in the analyzed detail region.

Limit states and crack width calculation

Assessment of the structure using the CSFM is performed by two different analyses: one for serviceability and one for ultimate limit state load combinations. The serviceability analysis assumes that the ultimate behavior of the element is satisfactory, and the yield conditions of the material will not be reached at serviceability load levels. This approach enables the use of simplified constitutive models (with a linear branch of concrete stress-strain diagram) for serviceability analysis to enhance numerical stability and calculation speed. Therefore, it is recommended the use the workflow presented below, in which the ultimate limit state analysis is carried out as the first step.

Ultimate limit state analysis

The different verifications required by specific design codes are assessed based on the direct results provided by the model. ULS verifications are carried out for concrete strength, reinforcement strength, and anchorage (bond shear stresses).

To ensure a structural element has an efficient design, it is highly recommended to run a preliminary analysis which takes into account the following steps:

- Choose a selection of the most critical load combinations.

- Calculate only Ultimate Limit State (ULS) load combinations.

- Use a coarse mesh (by increasing the multiplier of the default mesh size in Setup (Fig. 19)).

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 19\qquad Mesh multiplier.}}}\]

Such a model will calculate very quickly, allowing designers to review the detailing of the structural element efficiently and re-run the analysis until all verification requirements are fulfilled for the most critical load combinations. Once all the verification requirements of this preliminary analysis are fulfilled, it is suggested that the complete ultimate load combinations be included and the use of fine mesh size (the mesh size recommended by the program). User can change mesh size by the multiplier, which can reach values from 0.5 to 5 (Fig. 19).

The basic results and verifications (stress, strain, and utilization (i.e., the calculated value/limit value from the code), as well as the direction of principal stresses in the case of concrete elements) are displayed by means of different plots where compression is generally presented in red and tension in blue. Global minimum and maximum values for the entire structure can be highlighted as well as minimum and maximum values for every user-defined part. In a separate tab of the program, advanced results such as tensor values, deformations of the structure, and reinforcement ratios (effective and geometric) used for computing the tension stiffening of reinforcing bars can be shown. Furthermore, loads and reactions for selected combinations or load cases can be presented.

Serviceability limit state analysis

SLS assessments are carried out for stress limitation, crack width, and deflection limits. Stresses are checked in concrete and reinforcement elements according to the applicable code in a similar manner to that specified for the ULS.

The serviceability analysis contains certain simplifications of the constitutive models which are used for ultimate limit state analysis. A perfect bond is assumed, i.e., the anchorage length is not verified at serviceability. Furthermore, the plastic branch of the stress-strain curve of concrete in compression is disregarded, while the elastic branch is linear and infinite. These simplifications enhance the numerical stability and calculation speed, and do not reduce the generality of the solution as long as the resultant material stress limits at serviceability are clearly below their yielding points (as required by standards). Therefore, the simplified models used for serviceability are only valid if all verification requirements are fulfilled.

Crack width calculation and Tension stiffening

Crack width calculation

There are two ways of computing crack widths - stabilized and non-stabilized cracking. According to the geometrical reinforcement ratio in each part of the structure is decided, which type of crack calculation model will be used (TCM for stabilized cracking and POM for non-stabilized cracking model).

\( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 20 \qquad Crack width calculation: (a) considered crack kinematics; (b) projection of crack kinematics into the principal}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{directions of the reinforcing bar; (c) crack width in the direction of the reinforcing bar for stabilized cracking; (d) cases with}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{local non-stabilized cracking regardless of the reinforcement amount; (e) crack width in the direction of the reinforcing bar}}}\)\( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{for non-stabilized cracking.}}}\)

While the CSFM yields a direct result for most verifications (e.g., member capacity, deflections…), crack width results are calculated from the reinforcement strain results directly provided by FE analysis following the methodology described in Fig. 20. A crack kinematic without slip (pure crack opening) is considered (Fig. 20a), which is consistent with the main assumptions of the model. The principal directions of stresses and strains define the inclination of the cracks (θr = θs= θe). According to (Fig. 20b), the crack width (w) can be projected in the direction of the reinforcing bar (wb), leading to:

\[w = \frac{w_b}{\cos\left(θ_r + θ_b - \frac{π}{2}\right)}\]

where θb is the bar inclination.

Please note, that the program displays values of θr and θb < π/2. It means that the previous equation works for cases, where the reinforcement and crack go through the different quadrants of the Cartesian coordinate system as shown in Fig. 20, where reinforcement goes through I. and III. quadrants and crack through II and IV. For cases where the reinforcement and crack go through the same quadrants, the equation has to be modified as follows:

\[w = \frac{w_b}{\cos\left(-θ_r + θ_b + \frac{π}{2}\right)}\]

The component wb is consistently calculated based on the tension stiffening models by integrating the reinforcement strains. For those regions with fully developed crack patterns, the calculated average strains (em) along the reinforcing bars are directly integrated along the crack spacing (sr), as indicated in (Fig. 20c). While this approach to calculating the crack directions does not correspond to the real position of the cracks, it still provides representative values that lead to crack width results that can be compared to code-required crack width values at the position of the reinforcing bar.

Special situations are observed at concave corners of the calculated structure. In this case, the corner predefines the position of a single crack that behaves in a non-stabilized fashion before additional adjacent cracks develop. These additional cracks generally develop after the serviceability range (Mata-Falcón 2015), which justifies calculating the crack widths in such a region as if they were non-stabilized (Fig. 21).

\[ \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 21\qquad Definition of the region at concave corners in which the crack width is computed as if it were non-stabilized.}}}\]

Tension stiffening

The implementation of tension stiffening distinguishes between cases of stabilized and non-stabilized crack patterns. In both cases, the concrete is considered fully cracked before loading by default.

\( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 22\qquad Tension stiffening model: (a) tension chord element for stabilized cracking with distribution of bond shear,}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{steel and concrete stresses, and steel strains between cracks, considering average crack spacing); (b) pull-out assumption}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{for non-stabilized cracking with distribution of bond shear and steel stresses and strains around the crack; (c) resulting}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{tension chord behavior in terms of reinforcement stresses at the cracks and average strains for European B500B steel;}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{(d) detail of the initial branches of the tension chord response.}}}\)

Stabilized cracking

In fully developed crack patterns, tension stiffening is introduced using the Tension Chord Model (TCM) (Marti et al. 1998; Alvarez 1998) – Fig. 22a – which has been shown to yield excellent response predictions in spite of its simplicity (Burns 2012). The TCM assumes a stepped, rigid-perfectly plastic bond shear stress-slip relationship with τb = τb0 =2 fctm for σs ≤ fy and τb =τb1 = fctm for σs > fy. Treating every reinforcing bar as a tension chord – Fig. 22b and Fig. 22a – the distribution of bond shear, steel, and concrete stresses and hence the strain distribution between two cracks can be determined for any given value of the maximum steel stresses (or strains) at the cracks.

For sr = sr0, a new crack may or may not form because at the center between two cracks σc1 = fct. Consequently, the crack spacing may vary by a factor of two, i.e., sr = λsr0, with l = 0.5…1.0. Assuming a certain value for λ, the average strain of the chord (εm) can be expressed as a function of the maximum reinforcement stresses (i.e., stresses at the cracks, σsr). For the idealized bilinear stress-strain diagram for the reinforcing bare bars considered by default in the CSFM, the following closed-form analytical expressions are obtained (Marti et al. 1998):

\[\varepsilon_m = \frac{\sigma_{sr}}{E_s} - \frac{\tau_{b0}s_r}{E_s Ø}\]

\[\textrm{for}\qquad\qquad\sigma_{sr} \le f_y\]

\[{\varepsilon_m} = \frac{{{{\left( {{\sigma_{sr}} - {f_y}} \right)}^2}Ø}}{{4{E_{sh}}{\tau _{b1}}{s_r}}}\left( {1 - \frac{{{E_{sh}}{\tau_{b0}}}}{{{E_s}{\tau_{b1}}}}} \right) + \frac{{\left( {{\sigma_{sr}} - {f_y}} \right)}}{{{E_s}}}\frac{{{\tau_{b0}}}}{{{\tau_{b1}}}} + \left( {{\varepsilon_y} - \frac{{{\tau_{b0}}{s_r}}}{{{E_s}Ø}}} \right)\]

\[\textrm{for}\qquad\qquad{f_y} \le {\sigma _{sr}} \le \left( {{f_y} + \frac{{2{\tau _{b1}}{s_r}}}{Ø}} \right)\]

\[ \varepsilon_m = \frac{f_s}{E_s} + \frac{\sigma_{sr}-f_y}{E_{sh}} - \frac{\tau_{b1} s_r}{E_{sh} Ø}\]

\[\textrm{for}\qquad\qquad\left(f_y + \frac{2\tau_{b1}s_r}{Ø}\right) \le \sigma_{sr} \le f_t\]

where:

Esh the steel hardening modulus Esh = (ft – fy)/(εu – fy /Es) ,

Es modulus of elasticity of reinforcement,

Ø reinforcing bar diameter,

sr crack spacing,

σsr reinforcement stresses at the cracks,

σs actual reinforcement stresses,

fy yield strength of reinforcement.

The Idea StatiCa Detail implementation of the CSFM considers average crack spacing by default when performing computer-aided stress field analysis. The average crack spacing is considered to be 2/3 of the maximum crack spacing (λ = 0.67), which follows recommendations made on the basis of bending and tension tests (Broms 1965; Beeby 1979; Meier 1983). It should be noted that calculations of crack widths consider a maximum crack spacing (λ = 1.0) in order to obtain conservative values.

The application of the TCM depends on the reinforcement ratio, and hence the assignment of an appropriate concrete area acting in tension between the cracks to each reinforcing bar is crucial. An automatic numerical procedure has been developed to define the corresponding effective reinforcement ratio (ρeff = As/Ac,eff) for any configuration, including skewed reinforcement (Fig. 23).

\( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{Fig. 23\qquad Effective area of concrete in tension for stabilized cracking: (a) maximum concrete area that can be activated;}}}\) \( \textsf{\textit{\footnotesize{(b) cover and global symmetry condition; (c) resultant effective area.}}}\)

Non-stabilized cracking

Cracks existing in regions with geometric reinforcement ratios lower than ρcr, i.e., the minimum reinforcement amount for which the reinforcement is able to carry the cracking load without yielding, are generated by either non-mechanical actions (e.g. shrinkage) or the progression of cracks controlled by other reinforcement. The value of this minimum reinforcement is obtained as follows:

\[{\rho _{cr}} = \frac{{{f_{ct}}}}{{{f_y} - \left( {n - 1} \right){f_{ct}}}}\]

where:

fy reinforcement yield strength,

fct concrete tensile strength,

n modular ratio, n = Es / Ec .

For conventional concrete and reinforcing steel, ρcr amounts to approximately 0.6%.

For stirrups with reinforcement ratios below ρcr, cracking is considered to be non-stabilized and tension stiffening is implemented by means of the Pull-Out Model (POM) described in Fig. 22b. This model analyzes the behavior of a single crack considering no mechanical interaction between separate cracks, neglecting the deformability of concrete in tension and assuming the same stepped, rigid-perfectly plastic bond shear stress-slip relationship used by the TCM. This allows the reinforcement strain distribution (εs) in the vicinity of the crack to be obtained for any maximum steel stress at the crack (σsr) directly from equilibrium. Given the fact that the crack spacing is unknown for a non-fully developed crack pattern, the average strain (εm) is computed for any load level over the distance between points with zero slip when the reinforcing bar reaches its tensile strength (ft) at the crack (lε,avg in Fig. 22b), leading to the following relationships:

The proposed models allow the computation of the behavior of bonded reinforcement, which is finally considered in the analysis. This behavior (including tension stiffening) for the most common European reinforcing steel (B500B, with ft / fy = 1.08 and εu = 5%) is illustrated in Fig. 22c-d.

Structural element checks according to Eurocode

Assessment of the structure using the CSFM is performed by two different analyses: one for serviceability, and one for ultimate limit state load combinations. The serviceability analysis assumes that the ultimate behavior of the element is satisfactory, and the yield conditions of the material will not be reached at serviceability load levels. This approach enables the use of simplified constitutive models (with a linear branch of concrete stress-strain diagram) for serviceability analysis to enhance numerical stability and calculation speed.

References

ACI Committee 318. 2009a. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-08) and Commentary. Farmington Hills, MI: American Concrete Institute.

Alvarez, Manuel. 1998. Einfluss des Verbundverhaltens auf das Verformungsvermögen von Stahlbeton. IBK Bericht 236. Basel: Institut für Baustatik und Konstruktion, ETH Zurich, Birkhäuser Verlag.

Beeby, A. W. 1979. “The Prediction of Crack Widths in Hardened Concrete.” The Structural Engineer 57A (1): 9–17.

Broms, Bengt B. 1965. “Crack Width and Crack Spacing In Reinforced Concrete Members.” ACI Journal Proceedings 62 (10): 1237–56. https://doi.org/10.14359/7742.

Burns, C.. 2012. “Serviceability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Members Based on the Tension Chord Model.” IBK Report Nr. 342, Zurich, Switzerland: ETH Zurich.

Crisfield, M. A. 1997. Non-Linear Finite Element Analysis of Solids and Structures. Wiley.

European Committee for Standardization (CEN). 2015. 1 Eurocode 2: Design of concrete structures - Part 1-1: General rules and rules for buildings. Brussels: CEN, 2005.

Fernández Ruiz, M., and A. Muttoni. 2007. “On Development of Suitable Stress Fields for Structural Concrete.” ACI Structural Journal 104 (4): 495–502.

Kaufmann, W., J. Mata-Falcón, M. Weber, T. Galkovski, D. Thong Tran, J. Kabelac, M. Konecny, J. Navratil, M. Cihal, and P. Komarkova. 2020. “Compatible Stress Field Design Of Structural Concrete. Berlin, Germany.”AZ Druck und Datentechnik GmbH, ISBN 978-3-906916-95-8.

Kaufmann, W., and P. Marti. 1998. “Structural Concrete: Cracked Membrane Model.” Journal of Structural Engineering 124 (12): 1467–75. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9445(1998)124:12(1467).

Kaufmann, W.. 1998. “Strength and Deformations of Structural Concrete Subjected to In-Plane Shear and Normal Forces.” Doctoral dissertation, Basel: Institut für Baustatik und Konstruktion, ETH Zürich. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-7612-4.

Konečný, M., J. Kabeláč, and J. Navrátil. 2017. Use of Topology Optimization in Concrete Reinforcement Design. 24. Czech Concrete Days (2017). ČBS ČSSI. https://resources.ideastatica.com/Content/06_Detail/Verification/Articles/Topology_optimization_US.pdf.

Marti, P. 1985. “Truss Models in Detailing.” Concrete International 7 (12): 66–73.

Marti, P. 2013. Theory of Structures: Fundamentals, Framed Structures, Plates and Shells. First edition. Berlin, Germany: Wiley Ernst & Sohn.

http://sfx.ethz.ch/sfx_locater?sid=ALEPH:EBI01&genre=book&isbn=9783433029916.

Marti, P., M.Alvarez, W. Kaufmann, and V. Sigrist. 1998. “Tension Chord Model for Structural Concrete.” Structural Engineering International 8 (4): 287–298.

https://doi.org/10.2749/101686698780488875.

Mata-Falcón, J. 2015. “Serviceability and Ultimate Behaviour of Dapped-End Beams (In Spanish: Estudio Del Comportamiento En Servicio y Rotura de Los Apoyos a Media Madera).” PhD thesis, Valencia: Universitat Politècnica de València.

Meier, H. 1983. “Berücksichtigung Des Wirklichkeitsnahen Werkstoffverhaltens Beim Standsicherheitsnachweis Turmartiger Stahlbetonbauwerke.” Institut für Massivbau, Universität Stuttgart.

Navrátil, J., P. Ševčík, L. Michalčík, P. Foltyn, and J. Kabeláč. 2017. A Solution for Walls and Details of Concrete Structures. 24. Czech Concrete Days.

Schlaich, J., K. Schäfer, and M. Jennewein. 1987a. “Toward a Consistent Design of Structural Concrete.” PCI Journal 32 (3): 74–150.

Vecchio, F.J., and M.P. Collins. 1986. “The Modified Compression Field Theory for Reinforced Concrete Elements Subjected to Shear.” ACI Journal 83 (2): 219–31.